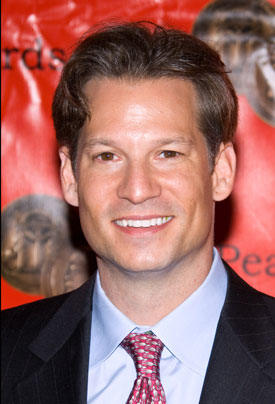

Richard Engel, Chief Foreign Correspondent for NBC News

Richard Engel at the end of a reporting trip in Syria in July 2012. Credit: NBC News

Richard Engel, author and Chief Foreign Correspondent for NBC News, is a natural storyteller. Irreverent and irrepressible, he’s made his passion his life, roaming the globe covering war zones, mostly the huge upheavals in the Middle East. Why? As he puts it, he wants to “be there to see the train of history as it roars through.”

Engel has virtually straddled that train no matter how hard or risky. He recently escaped being held hostage in Syria. He’s learned to think clearly with a gun to his head. He didn’t lose sleep when his hotel room was blown up in Iraq. The roadside IEDs have fortunately not gone off under him. Everywhere, from the Arab Spring countries to Afghanistan, the bullets have missed him. Engel has said he has to do his work as though his blue bulletproof vest has a target on it. And he does his work very well. At age 40 there are few awards he hasn’t already won— seven News & Documentary Emmy Awards, the George Foster Peabody Award, two Edward R. Murrow Awards, the Medill Medal for Courage in Journalism, and the Daniel Pearl Award, are among his accolades. But where does a guy like this get that grit and determination?

At a Speak Up for Children event in New York City on May 17, 2013, naturally crackling with intelligence and intensity, Engel gave a small audience a peek at how his courage formed. He took them through a painful conflict of a different sort: his own, as a small child, with a brain he couldn’t seem to corral and he didn’t know why. Engel has dyslexia, and then some. No one ever formally diagnosed him, but he said of grade school: “Nothing worked…. I would answer test questions and then the answers on the paper wouldn’t make any sense…. I could add five plus five and get Nebraska.”

“Nothing worked…. I would answer test questions and then the answers on the paper wouldn’t make any sense…. I could add five plus five and get Nebraska.”

Engel had only one person who really understood him, his mom. Privileged private schooling in New York City only heaped on additional expectations Engel couldn’t meet. Alienated young Richard had more fights than friends. He was flopping at all three R’s, his standardized testing was hopeless, and he was taken for a shirker. What it cost him was confidence. He said he had none. Whatever those teachers were trying to say, he didn’t get it and he couldn’t change that. Engel was sent to a child psychiatrist whom he said was useless. Thus began a lifelong disdain for the profession which Engel refused to disguise, despite being interviewed at the event by the well-known psychiatrist Dr. Harold S. Koplewicz —much to the amusement of the audience.

Frustrated and angry, Engel would create his own first break heading into 7th grade. He became a leader. For the first time in his life he found inspiration by throwing himself in over his head and learning that if life was sink or swim, he was a pretty good swimmer.

Engel continued summers at the camp and defiantly shifted his view of the schoolwork he couldn’t do. Maybe it was the work that was a boring waste of time. If he didn’t understand what the teachers were teaching, maybe it wasn’t worth understanding. Somewhere along the way, he slyly told the audience, he threatened to kill that same childhood psychiatrist (the audience roared). Engel became increasingly confident with puberty and said somehow with confidence the class work improved. By high school, he had a new setting and girls. His confidence snowballing, Richard Engel became a handsome guy with some better grades and popularity.

Richard Engel attends the 2009 Peabody Awards. Credit: AP Photo/Charles Sykes

His next big leap over his learning disabilities and low self-esteem was a high school junior year abroad. It’s long been a myth that dyslexics can’t learn foreign languages. Engel went to Italy, immersed himself in both the country and an Italian romance and came back fluent in Italian, with a lifelong love for international travel.

All of Engel’s moves outside the claustrophobic confines of the school had worked well for him. Languages would be the same. Engel would go on to pick up four different dialects of Arabic as well as Spanish and Italian—none of them learned anywhere near a classroom. He explained about how he picked up language in a totally foreign environment: “If you can stand to listen to the chaos long enough you can start picking out the notes and soon you have a symphony.”

Despite admittedly rotten SAT scores Engel got into Stanford University. Like most of his other academic experiences he found it disappointing (“I didn’t think it was as beautiful as everybody said…. To me it looked like a lot of strip malls….”). In college, he’d hoped to find students discussing Plato late into the night. Instead he found a bunch of kids inventing their own computers.

He spent his college summers working cruise ships for the travel and the cash. His jobs included “charming old ladies” for tips, he said to his amused audience. He tried one summer internship at CNN in New York and hated it. He said he simply could not work behind a desk. Engel majored in International Relations, graduated, married, and traded domestic comfort for a seven-story walk-up in Cairo as a freelance journalist. He had not a word of the language yet, nor a single job prospect, and precious little savings. Again, Engel went in way over his head. He stumbled his way into print and radio journalism from the ground up.

His break into television came seven years later when, true to form, he threw himself in over his head during the “Shock and Awe” American bombing of Baghdad. The American television networks had pulled most of their people out for safety reasons, but there was Richard Engel, still in Baghdad, reporting for ABC News. On camera for the first time in his life, he was patiently being coached through it on the air by anchorman Peter Jennings. Engel’s helmet askew, his body involuntarily wincing at the incoming bombs, he looked like he might not last a day. Instead, ABC kept him on because he knew more than anyone else and spoke Arabic. Engel became a television pro in short order, and would be the only TV reporter to stick it out for the entire length of the Iraq war. Engel’s marriage was a casualty, however, and he has said he realized he is really married to his job. Says Engel now about his leaps and line of work: “If you don’t take any risks you risk losing out on life.”

“I think it’s a gift,” he said with a wry smile. “I mean, who wants to think like everybody else?”

His advice to parents of dyslexic kids? “Allow them to get into environments where they are on their own. Don’t coddle your kids. Let them respect their own fear. Help them find something they are good at.” After his long inner battle to get along with his brain, Engel says he still reads slowly and he hears his own voice when he reads. But that hasn’t stopped him from writing two books and speaking into live cameras under the most stressful conditions possible.

Looking back it’s clear when Engel couldn’t find something he loved, he kept widening his search until it included the whole world. It’s also clear listening to him now that he loves the life he leads and no other would do. He’s also realized that seeing things differently from other people has its benefits. “I think it’s a gift,” he said with a wry smile. “I mean, who wants to think like everybody else?” Certainly not Richard Engel.

As for his supportive mother, no matter where he is in the world, he still speaks to her every day.

By Jane Wallace

Related

Blake Charlton, M.D., Author & Cardiologist Fellow at the University of California, S..

Blake Charlton would appear to have it all. A summa cum laude graduate of Yale University, a graduate of Stanford Medical School, and a published author, whose debut novel, Spellwright, was released to glowing reviews from the science fiction community and the publishing industry at large. The novel was the first of a nearly finished trilogy published by Tor Books. Set in a world where words can be physically peeled off a page and used to cast spells, Spellwright relates the misadventures of a wizard named Nicodemus Weal, who has a gift for producing magical language, but a disability that makes any text he touches misspell, with devastating consequences.

Read More

Max Brooks, New York Times Best-Selling Author

Max Brooks, the #1 New York Times bestselling author of The Zombie Survival Guide (Three Rivers Press) and World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War (Crown) knows a little something about this. Yet he would argue that his years spent at the Center for Early Education in Hollywood as a young boy with dyslexia left him riddled with anxiety and self-doubt that shadows him to this day. “It was a slog,” he says simply.

Read More

Jeanne Betancourt, Children’s Book Author & Screenwriter

Jeanne Betancourt is the author of 75 novels for children and young adults; more than a dozen film and television scripts; and an adult nonfiction book. She is a recipient of the American Psychological Association’s National Psychological Award for Excellence in the Media and several Children’s Choice Awards. Betancourt also received six Emmy Award nominations for her After-School Specials, written for ABC Television and featuring teens dealing with critical social issues.

Read More

Octavia Butler, Award-Winning Author

Octavia Butler was an award-winning author of thirteen books. She was a pioneer in the science fiction genre, winning both the Nebula and the Hugo Awards. In 1995, Butler was honored with a MacArthur fellowship, and in 2005, she was the recipient of the City College of New York’s Langston Hughes Medal. The Pen Center West awarded her with a lifetime achievement award. She died after a fall outside of her home in 2006.

Read More