Max Brooks, New York Times Best-Selling Author

By Sue Glader

“My coping mechanism with my dyslexia is to use wit and humor.”

— Max Brooks

It’s hard to imagine anything worse than being in the vicinity of a clot of undead zombies, what with all those decaying limbs and relentless urges to eat you for dinner.

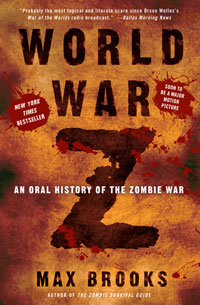

But Max Brooks, the #1 New York Times bestselling author of The Zombie Survival Guide (Three Rivers Press) and World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War (Crown) knows a little something about this. Yet he would argue that his years spent at the Center for Early Education in Hollywood as a young boy with dyslexia left him riddled with anxiety and self-doubt that shadows him to this day. “It was a slog,” he says simply.

“I was an idiot,” Brooks explains, describing how he saw himself before his diagnosis at age eight. “I still am. That doesn’t change. Once your self-esteem nosedives, I think it’s very rare that it ever comes back to where it was. No matter what I accomplish, I’m still the kid who had to study for two hours a night, coming in to take an untimed test, praying to God that I pulled off a C.”

Humor Me

Yet Brooks is an articulate and easy conversationalist, peppering a discussion with researched insight, anecdotes, and funny asides. This is not surprising, since Max is the only child of actress Anne Bancroft and legendary comedian/actor/writer/director Mel Brooks. “My coping mechanism with my dyslexia is to use wit and humor.”

“But my teachers were convinced I was lazy,” Brooks goes on to say. “I think my having famous parents allowed them to create a narrative that I was a spoiled brat, that my parents would bail me out.” He remembers at one point being so frustrated at his own inability to do the work that he just cried in front of his teacher. Her response burned. “She said, ‘You can do it. You just don’t want to.’”

“My mom met with my teachers every year, to try and make them see this was not an issue of won’t but can’t.”

The Issue of Won’t vs. Can’t

His own mother knew better. She saw how he mixed up his letters and jumbled his words. So Bancroft took him to the Marianne Frostig Center in Pasadena and had him tested for dyslexia, a test that confirmed young Max was, indeed, dyslexic (passing with flying colors).

Armed with a diagnosis, she got to work on Max’s behalf. “My mom met with my teachers every year, to try and make them see this was not an issue of won’t but can’t.”

And that, for Brooks as well as countless other children with dyslexia, is at the heart of protecting their own self-image. He was trying so hard. He wanted to do well. Why couldn’t he be just be like everyone else?

“There are ways to get dyslexic children to do as much work as all the other kids—to learn as much and work as hard—but not in the exact same way,” he says. “If you try to force them, the damage to their self-esteem, in many cases, is irreparable.”

High Anxiety

For Brooks, he couldn’t get out from under his own anxiety. Even untimed tests were painful. “I think only 25% of my problems in school were caused by dyslexia, but the other 75% was the anxiety” the dyslexia created. This was cumulative, persistently building inside of him. “So when it came time to sit down and take a test, my anxiety was so through the roof, it just clouded everything else.”

Brooks’s mother made sure he was tutored every day, sometimes for two hours at a stretch. And, perhaps most important, Bancroft learned that young Max took information in verbally. To help, she gathered his reading lists from school and had the Braille Institute of America turn them into books on tape.

“I listened to my books, otherwise I never would have gotten through school,” Brooks says matter-of-factly. To this day, when Brooks is doing research for his books, he often buys both the printed and audio version. He’ll listen to the audio while reading along with the hard copy. Whenever an important fact comes up, he’ll pause the audio and highlight the page. “I find that to be a very helpful coping mechanism.”

“There are ways to get dyslexic children to do as much work as all the other kids—to learn as much and work as hard—but not in the exact same way.”

Gets Better with Age

While Brooks was accepted at the rigorous Pomona College, the grind of constant struggle, academic inadequacy, and “putting 110 percent in and getting 10 percent out” for his entire academic life had taken its toll. “I was so burnt out.” He chose what he perceived to be the easy route, attending Pitzer College, and received a bachelor’s degree in history.

But it was later, in graduate school, that Brooks began to chip away at his unyielding academic unease. “I had made a conscious choice as a responsible young adult to go to graduate school (studying film at American University in D.C.). I knew why I was going. I knew what the goal was. And I owned it all. I was a volunteer, as opposed to elementary school and high school, when I was essentially a draftee.”

His anxiety dropped, learning happened naturally, and instead of being flattened by fear, “I would sit down to take very complex technical tests—about color temperature and photographic speed, really mechanical stuff—and I aced them.”

Brooks went on to win an Emmy as a writer for Saturday Night Live, acted both in television and for voice-over roles, but realized his true calling was combining his insatiable appetite for history with his natural gift of telling a compelling story. Having written short stories and even long ones (400 pages during his 9th grade year) for fun as a young man, Brooks wanted to be a paid novelist. And his area of fascination was hardly mainstream.

Big Picture Thinker

There’s been a lot written about the ability of those with dyslexia to see things in a broader context. The entrepreneurial ranks are filled with dyslexics, applying creative solutions to everything from design to finance to medicine and science.

Brooks zeroed in on zombies. His first book, The Zombie Survival Guide, was seemingly written with his tongue planted firmly in cheek, yet was filled with rather concrete preparedness advice.

Then having grown tired of only seeing small group zombie adventure stories, his love of world history spurred him to consider a global zombie plague and the implications of such a worldwide event. “How would our government react? Or how would other governments react?” he asks. “World War Z is me thinking big picture.”

And yes, he can tell you the best way to survive a zombie attack (“Use your head; cut off theirs”), the best protection (“tight clothes and short hair”), and the importance of staying hydrated, but there is a strong subtext even to this relatively straightforward subject matter.

“A zombie story gives people a fictional lens to see the real problems of the world,” he told The New York Times. “You can deal with societal breakdown, famine, disease, chaos in the streets, but as long as the catalyst for all of them is zombies, you can still sleep.”

They Can Handle the Truth

That kind of thinking has intrigued the top brass at places like the Naval War College, where Brooks has been a featured speaker. Replace zombies with, for example, a natural disaster or a disease outbreak like SARS, and, as Brooks was recently told by the president of the war college, “It’s a credible global disaster collapse scenario.” He is one civilian that the U.S. Army division responsible for homeland defense, the Fifth Army, enjoys hearing from.

“I’m starting to see why people have sunk and why people have swum. A lot of the kids who skated through life, where things came easily to them, have never had to struggle. They’ve never had to create coping mechanisms. They’ve never had to compensate for any sort of weakness, and it made them much less resistant to adversity.”

Because of a horrid experience when he was 10, where pint-sized hecklers made him feel so small as he tried to read aloud a passage on John F. Kennedy, Brooks refuses to read speeches, even to military generals. “Either I memorize my speeches, or I just walk out and start talking. I never ever read when I address people.”

This means that Brooks is incredibly engaging as well as nimble on stage, to say nothing of being deeply prepared in his subject matter. He’s turned a humiliating struggle into a coveted skill.

Civil Rights and Comic Books

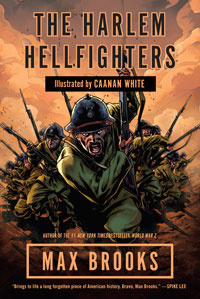

Brooks’s newest book, published in April 2014, is called The Harlem Hellfighters (Broadway Books), a graphic novel completely illustrated by Canaan White. It is based on the true story of the first African-American infantry regiment to fight in WWI. Despite extraordinary struggles starting in basic training and extending to the battlefield and discrimination at home (sound familiar?), they emerge as one of the most successful yet least appreciated or decorated regiments of the war, never losing a foot of ground to the enemy or a man to capture. Movie rights have just been optioned by Will Smith.

“It’s a long way for a kid who could barely read in elementary school,” he quips.

Not one to sit still for long, Brooks is already working on a comic book series pitting vampires against zombies. But of course, for Brooks, there is significant subtext to the subject.

“It’s going to deal directly with the psychological aspects of dyslexia, namely how our greatest supposed weaknesses can be our greatest strengths, and vice versa.” He explains that vampires are unfamiliar with struggle; they are inherently strong and unafraid, never having had to adapt to their surroundings. In Brooks’s mind, they are the natural athlete or the kid who had no problems in school. But their only food source—humans—is being eaten out from under them. “They don’t know what to do, because they’ve had no history of struggle.”

Survival of the Fittest

He’s able to write this fantasy comic because he’s seen this scenario play out in real life, having kept in touch with many people from his childhood. “I’m starting to see why people have sunk and why people have swum. A lot of the kids who skated through life, where things came easily to them, have never had to struggle. They’ve never had to create coping mechanisms. They’ve never had to compensate for any sort of weakness, and it made them much less resistant to adversity. Kids who have had to struggle in early life can get comfortable with struggling. When adversity comes knocking in their 30s and 40s and 50s, well, they know how to overcome, whereas the kids who never had to study, always got straight As, never went to class. . . .”

He trails off. It seems like these are the kids for whom Max Brooks wrote The Zombie Survival Guide. The other kids—the ones like him in school?

Why, they’re natural-born survivors.

Related

Blake Charlton, M.D., Author & Cardiologist Fellow at the University of California, S..

Blake Charlton would appear to have it all. A summa cum laude graduate of Yale University, a graduate of Stanford Medical School, and a published author, whose debut novel, Spellwright, was released to glowing reviews from the science fiction community and the publishing industry at large. The novel was the first of a nearly finished trilogy published by Tor Books. Set in a world where words can be physically peeled off a page and used to cast spells, Spellwright relates the misadventures of a wizard named Nicodemus Weal, who has a gift for producing magical language, but a disability that makes any text he touches misspell, with devastating consequences.

Read More

Jeanne Betancourt, Children’s Book Author & Screenwriter

Jeanne Betancourt is the author of 75 novels for children and young adults; more than a dozen film and television scripts; and an adult nonfiction book. She is a recipient of the American Psychological Association’s National Psychological Award for Excellence in the Media and several Children’s Choice Awards. Betancourt also received six Emmy Award nominations for her After-School Specials, written for ABC Television and featuring teens dealing with critical social issues.

Read More

Octavia Butler, Award-Winning Author

Octavia Butler was an award-winning author of thirteen books. She was a pioneer in the science fiction genre, winning both the Nebula and the Hugo Awards. In 1995, Butler was honored with a MacArthur fellowship, and in 2005, she was the recipient of the City College of New York’s Langston Hughes Medal. The Pen Center West awarded her with a lifetime achievement award. She died after a fall outside of her home in 2006.

Read More

Gareth Cook, Pulitzer Prize-Winning Journalist

Gareth Cook is a journalist and is currently a writer for The New Yorker and a series editor at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. He spent seven years as the Boston Globe’s science editor reporter, and during that time won the Pulitzer Prize (2005), the National Academy of Sciences Communications Award (2005), and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Ocean Science Journalism Award (2005). In awarding the Pulitzer to Cook, the judges commended him for “explaining, with clarity and humanity, the complex scientific and ethical dimensions of stem-cell research.”

Read More