A Charter School’s Journey into Assistive Technology

By Joshua Jenkins

In the beginning…

At the end of last school year, my special education coordinator, Susan, asked my colleagues and me what we wanted for the 2011–2012 school year. “A big raise,” a couple of us shouted, half-kidding. After the laughter subsided, we answered her in earnest. Someone turned to Susan and whispered, “We need iPads.” She brushed it off. “Everyone needs iPads,” she said. “I need an iPad, too!” She quickly realized my colleagues were not fooling, not even a little; they were serious about iPads. I was with Susan; I wasn’t sure what good an iPad would be in the classroom other than a way for kids (and teachers) to play, get off task, and inevitably get in trouble. My skepticism didn’t last. At the meeting, I felt that I had been all but stoned by my fellow special education teachers who were evangelical about iPads. At the end of this meeting, iPads were in the special education budget, and I was a believer.

A few months down the road, in August, we were all pumped up and energized from a summer break and a few weeks of professional development before school—but we were iPad-less. They hadn’t been ordered. We were wimpy about asking the school to purchase iPads, afraid that the rest of the staff would think we were sitting in first class and leaving them behind in coach. Susan hadn’t given up, though. With determination, she sought out an assistive technology consultant to help us with using more technology in our classroom. Assistive technology, AT in jargon, refers to any technology or supportive device that helps enable students: something as small as a pencil grip or as fancy as an iPad.

In a few weeks, this consultant came to meet with each of the special education teachers one-on-one with a goal of ultimately guiding us to some technology that would be most appropriate for our kids. iPads came up; the consultant gave us what looked like a 10,000-pound encyclopedia of iPad apps for education: everything from an app to help motivate kids with toilet-training to augmentative communication device apps to sight word and math flash card apps. She also recommended some lower-tech items like special paper to use for math computations and putting spaces between words in writing. She also demo-ed a word processor that has a text-predict feature—eliminating the painful step of physically writing or spelling words for kids who suffer from reading and learning disabilities like dyslexia and dysgraphia.

This was the moment of the assistive technology Big Bang—that enlightening moment at our charter school where the special education department’s framework of instruction began to re-work, re-think and re-imagine all the strategies and tools that AT would give us and how it would allow our students to reach higher potential.

iPads

It goes without saying that iPads are cool, and fun to play with. Everyone knows that. But when you first think about educational apps, you likely immediately have the same thought I did: “Nah, those apps are probably like a lot of free educational websites and games. They either go way too over the kids’ heads or they’re too low or they’re not well made. They’re just to play with.” This is a terrible misunderstanding.

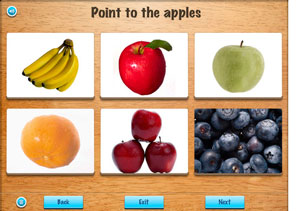

Let’s start with the See.Touch.Learn. app. This is a multipurpose app that can make lessons for very low-functioning kids who need help identifying colors or basic everyday objects; it is an app to learn sight words, an app to practice phonemic awareness skills, to practice math facts, or to categorize objects. This app can be whatever you want it to be. The app itself is free and comes with a series of libraries that you can purchase (most $2.99 or under): anything from sight word libraries, body parts, food, shapes, colors, and actions words. Then, the teacher makes custom lessons with as few or as many tasks as he or she desires, and each task may have one choice or multiple choices. There can be more than one correct answer. The teacher may choose for the task to ask the student anything—you can record your own voice with any question you choose. Some lessons that I made for a struggling reader included, “Point to the words that rhyme with red.” Or, for another student who had trouble identifying high-frequency words, I made a lesson with questions like, “Choose the word that says ‘and,'” where the student chose between two or three words.

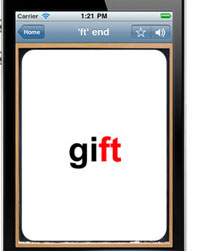

Another fabulous (and free) app for phonics and working with word patterns is Phonics Genius. Teachers may choose from a pre-loaded library of hundreds of word patterns or create a customized list of words for students. I had my students enter customized lists of the specific high-frequency words they needed to work on, and they recorded their own voices reading the words. Then, when they practice these flash cards, they press the sound button to see if they read the word correctly, and it reads the word to them in their own voice.

If struggling readers need help with word patterns, the ABC Writing app ($1.99) is another great tool. It also comes with a huge library of CVC (cat or hit), CVVC (rain or boat), and CVCe ( kite or bake) word patterns, but this app allows students to trace over the words to practice writing them as well. There is also a feature to hear the word spelled letter-by-letter as well as the whole word read. This app also includes three pen colors and music to help keep the student entertained.

For very low readers who are inevitably struggling writers, the Dragon Dictation app (free) is a terrific solution for recording responses to short-answer questions. This app is a speech-to-text app. If a student is not able to write a short-answer response independently, he or she may open a new note in Dragon and speak his/her answer into the iPad microphone. This allows the teacher to focus on the student’s comprehension of the material without forfeiting the rigor of work the student is capable of doing due to the student’s writing ability. This is obviously great for content-based subjects like reading comprehension, science, social studies, and justifying solutions to math problems.

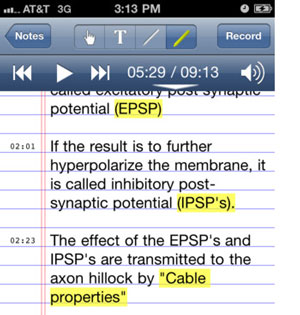

For fluency work, one of my colleagues has been successful having students record themselves reading on iPads using Audio Note (there’s a “lite” version for free). Based on my own experience and many conversations I have had with parents, we often try to tell our students how they sound when they read: “You sounded choppy here; you paused on this word.” The truth is that you could give these comments until you’re proverbially or literally blue in the face; but until a child really hears for herself how she sounds, she won’t have a clue about what you mean. The change in fluency from a small, repeated reading (for example, reading the same passage over and over) and hearing the progress from slow, choppy reading to smoother, faster reading is not just motivating to students. It allows them to see for themselves that, with practice, their reading and fluency will improve.

Similarly, another excellent fluency tool is Read To Kids ($0.99). The difference with this app is that students take the role of the narrator and record the entire story, pressing a large bell on the screen every time they begin a new page. Then, an audience or the child can listen to the book. As the audience/child listens, they know to turn the page every time the bell rings. This is exceptional because it conversely allows me to record an above-level story on iPads and then allows the students to independently follow along in the book as they listen—great for classroom learning centers or for a break. When students know they are recording for an audience to listen to later, they put their best foot forward

Toontastic is a free—and amazingly fun—app that allows students to make their own cartoons, which is a great activity for students who have mastered story elements (characters, setting, conflict, resolution, and dialogue). The app walks students through each step of the story process, and the students title and publish their cartoons.

Toontastic is a free—and amazingly fun—app that allows students to make their own cartoons, which is a great activity for students who have mastered story elements (characters, setting, conflict, resolution, and dialogue). The app walks students through each step of the story process, and the students title and publish their cartoons.

In addition to these, there are a number of other apps out there worth trying—not all apps are designed for all kids, but it doesn’t hurt to try them out—especially if they’re free or inexpensive (like all of these). There are an abundance of apps that read books to kids as well as many to make customized flash cards or come with pre-made flash cards. iPads are a first-rate tool for reaching students—and even though we’ve found some great apps, we’re just at the tip of the Apple iceberg.

Word Processors

Another huge piece of technology we began to use this year is word processors with text predict. The specific tool we are using is the NEO2 word processor from Renaissance Learning with Co:Writer by Don Johnston. Saying that this is a powerful tool for writing is a miserable understatement. As a special education teacher who was incredibly frustrated by knowing my students had wonderful, hilarious, and creative ideas that they couldn’t express due to the physical act of handwriting or extreme difficulty with spelling and reading, it hurt me to know my students’ confidence and enthusiasm for writing would suffer incredibly and that they would grow into adults who only wrote when they had to make a grocery list or send a text—and that even those acts of writing might be painful for them.

Luckily, for students with dyslexia, dysgraphia or other learning disabilities, Co:Writer eliminates the pain of spelling. Simply put, it predicts words. Students enter the beginning sound of the word they want, and it presents a list of 6 words to choose from. If they don’t see the word they need, they are able to either enter the next sound or to push the right arrow to see more words that begin with the same letter. When the students find the word they want, they don’t need to type it; they are simply able to select the number of the word they want, 1 through 6.

And, don’t worry. For students who really suffer with reading and cannot read the lists of words it presents, NEO has a text-to-speech option you can order. The text-to-speech device reads the list of words as students scroll through them. Even better, it also reads the students’ writing back to them—they can hear their writing, and they know if it sounds right. I use this feature with several students. They do, however, need to have a solid base of basic phonics and reading knowledge in order to spell beginning sounds and add a vowel sound if they don’t immediately find the word they need. Even factoring that in, it’s still a terrific tool. Two of my students in upper elementary grades, who read on a kindergarten level and were (“were” being the operative word!) non-writers, have been able to write simple paragraphs using the word processor with text-to-speech.

The confidence this tool gives struggling writers is inspirational. Seeing faces smile for the first time as they write instead of sighs and frustration was amazing. My students no longer lethargically walk in to writing class, taking minutes to find a pencil. They nearly run over one another trying to come in so they can sit down and get to the business of writing.

Low-tech

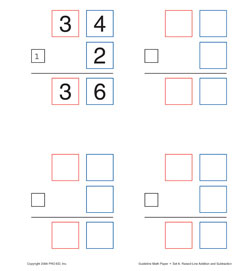

Let’s talk about the miracle of paper. For math, PRO-ED Inc. makes four different kinds of paper called “Guideline Math Paper,” one for each of the four different math operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division). Each paper has pre-made boxes and outlines for the steps required to complete an operation. The two-digit addition paper, for instance, has red boxes for the tens place, blue boxes for the ones place, and a black box above the tens place for carrying. Students are able to plug their numbers into the boxes and do the math without fear or worry of misaligning numbers or skipping the carrying step. This has been really helpful for some of our students who need reminders for the different and multiple steps of different math operations.

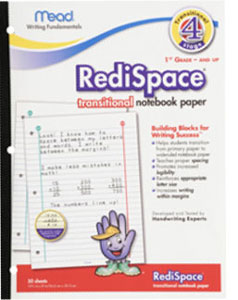

For writing, Mead makes a special paper (RediSpace) to help guide students who struggle to write in the margins or put appropriate spaces between words. On the left margin, there are green “go” signs, telling students to begin writing there on the line. At the right margin, there is a stop sign. To help with spacing, on every line of paper, there are small tick marks with just enough space between them for one letter, punctuation mark, or a space between words. This special feature of the paper allows students to visually see and understand what a space should look like. A lower elementary school teacher produced stunning work from her students when she began using this paper, and I also found it useful for a few of my upper elementary students who did not use correct spacing between words.

Another low-tech device that is usually used for helping with communication or speech and language therapy is Boardmaker by Mayer-Johnson. While we use this program with students who are nonverbal or have communication needs, it is also helpful for low readers. With Boardmaker, teachers design boards that match words or short phrases with a picture. Teachers are able to make boards that have a simple sentence or can make a board with a short story. Each word corresponds to a picture above it, aiding students in word solving.

Looking forward…

Right now at our school in New Orleans, assistive technology is helping motivate and teach our kids. It is allowing us to put a steering wheel into our students’ own hands; they’re driving their own learning, and as special education teachers, we’re getting to play the role of passenger—mentoring and giving feedback. We instruct, holding out the soccer mom arm when things don’t work and then adjust our instruction and the assistive technology strategies to reach students. As we delve more into the world of assistive technology and find strategies and devices, we understand we don’t know all the answers or have all the strategies. But, more important, I think we’ve taken the initiative and finally have the guts to experiment with technology, using AT to help kids see the academic growth they have the potential to make. They are learning that they are curious and creative scholars and that their disability is not always detrimental—it can be an asset. And that’s what makes a special piece of paper, an iPad, a word processor, or any enabling device a miracle.

Joshua Jenkins is a special education teacher at New Orleans College Prep Charter School. He is a Teach For America corps member. He attended Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. He holds a B.A. in English and is an aspiring writer.

Related

Case Study – How Morningside Elementary School Helps Dyslexic Students Succeed

Teacher training and a well-stocked toolbox help dyslexic students succeed at one Atlanta public school.

Read MoreDyslexia and Civil Rights: Making Room on the Bus for All Children

My early experiences have become my bridge to understanding dyslexia and the plight of students whose strengths go unnoticed in the classroom.

Read More

Building a word-rich life for Dyslexics

A confession: I get a significant thrill from reading research that confirms my personal suspicions.

Read More

How speech-to-text transformed a student’s 5th grade year

Last fall, the fifth graders in my class were the lucky recipients of iPads–one for each student.

Read More