Octavia Butler, Award-Winning Author

Octavia Butler was an award-winning author of thirteen books. She was a pioneer in the science fiction genre, winning both the Nebula and the Hugo Awards. In 1995, Butler was honored with a MacArthur fellowship, and in 2005, she was the recipient of the City College of New York’s Langston Hughes Medal. The Pen Center West awarded her with a lifetime achievement award. She died after a fall outside of her home in 2006.

Octavia Butler spent most of her 58 years of life crafting stories. The award-winning author of thirteen books, Butler was a pioneer in the science fiction genre, breaking through barriers as one of the few African Americans and the first woman to be a successful full-time writer in an arena of white males. Many in the literary world regard her novel, Kindred, as one of the modern classics; and it is often read and discussed in high school and college classrooms. In addition to winning the top prizes in the science fiction genre, the Nebula and the Hugo Awards, she was honored with a lifetime achievement award from PEN Center West and the Langston Hughes Medal from the City College of New York. In 1995 Butler and her work were recognized with a MacArthur Foundation fellowship, aka, “the Genius Grant.”

Octavia Butler spent most of her 58 years of life crafting stories. The award-winning author of thirteen books, Butler was a pioneer in the science fiction genre, breaking through barriers as one of the few African Americans and the first woman to be a successful full-time writer in an arena of white males. Many in the literary world regard her novel, Kindred, as one of the modern classics; and it is often read and discussed in high school and college classrooms. In addition to winning the top prizes in the science fiction genre, the Nebula and the Hugo Awards, she was honored with a lifetime achievement award from PEN Center West and the Langston Hughes Medal from the City College of New York. In 1995 Butler and her work were recognized with a MacArthur Foundation fellowship, aka, “the Genius Grant.”

But Octavia never considered herself to be very bright, much less a genius. In fact, she struggled in school, where teachers interpreted her slow reading and inability to finish assignments in the allotted time as an unwillingness to do the work. When given the time to write in school, Butler would weave tales that were so out-of-the-box her teacher assumed she had copied them from a published story. When she was thirteen, one teacher did recognize her talents as a writer and encouraged her to submit a short story to a science fiction magazine—he even typed it out for her. That story would be the first of many she submitted for publication, and would signify the moment Butler knew that she wanted to—and could—write for a living; however, Butler was writing stories for herself long before then.

A shy loner, Butler found solace and company in words. At as young as four years old, she was making up stories for herself; and as she recalls in an interview with the literary journal Callaloo, “By the time I was ten I was writing, and I carried a big notebook around so that whenever I had some time I could write in it. That way, I didn’t have to be lonely. I usually had very few friends, and I was lonely. But when I wrote I wasn’t, which was probably a good reason for my continuing to write as a young kid. I read a lot also, for the same reasons.1”

Despite her dyslexia, she was a bookworm, reading everything that she could find. Butler described how she got her first library card: “When I was six and was finally given books to read in school, I found them incredibly dull; they were Dick and Jane books. I asked my mother for a library card. I remember the surprised look on her face. She looked surprised and happy. She immediately took me to the library and got me a card. From then on the library was my second home.” Butler’s mother only had three years of education, but she learned to read, and worked hard as a housekeeper to make sure that her daughter learned to read and went to school. After high school, Butler went on to graduate from Pasadena City College with an Associates of Arts degree in 1968.

Butler continued writing, and also continued with school, going on to study at California State University in Los Angeles and the University of California, Los Angeles, and found her learning style, as she explained to Charlie Rose: “I learn better through listening than through reading. Which is one of the reasons I read so slowly—I hear every word and that way I can remember it. I get books on tape, and also courses on tape.2” Butler did take classes in writing, but also studied anthropology, psychology, physics, biology, and geology, among other subjects. “You’re always realizing there is so much out there that you don’t know,3” she observed. “That’s when I began to teach myself as opposed to just showing up at school. I think that there comes a time when you just have to do that, when things have to start to come together for you or you don’t really become an educated person.”

When she took a class with science fiction master Harlan Ellison at the Screen Writers’ Guild Open Door Program, Butler found her mentor and a path to realizing her life’s work. Ellison encouraged her to attend the Clarion Science Fiction Writer’s Workshop, and before the end of the workshop, she sold her first two short stories.

After a few years more of working odd jobs, writing, and receiving rejection letters, Butler took a shot at writing a novel, a task which proved daunting at first attempts. She persevered, and was successful—her manuscript was purchased by Doubleday, becoming the first novel in what became known as her “Patternist” trilogy. Twelve other books followed.

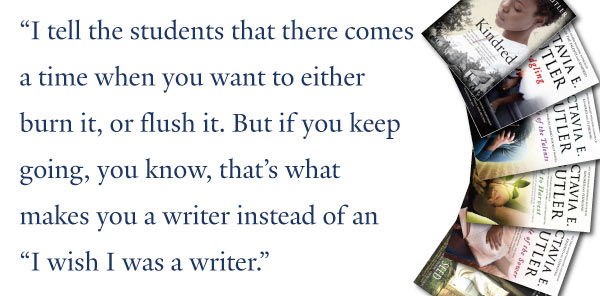

Butler, who suffered from health problems and was not physically fit, likened writing novels to her experiences hiking in the Grand Canyon and in Peru: “There will always come a time in writing a novel for instance, a long undertaking like that, when you don’t think you can do it. Or, you think it’s so bad you want to throw it away. I tell the students that there comes a time when you want to either burn it or flush it. But if you keep going, you know, that’s what makes you a writer instead of an ‘I wish I was a writer.’4”

Speaking on PBS’s Closer to the Truth, Butler described her own variation of the Hippocratic Oath: “‘Do the thing that you love and do it as well as you possibly can and be persistent about it.’ I think it’s really important to find a way to earn a living doing what you care about and trying to do as much good as you can.5” Octavia Butler certainly practiced what she preached, challenging the notions of who can make it as a writer; tackling issues such as race, sexuality, discrimination, and politics with her works; and sharing her stories, and her wisdom, with the public.

Footnotes

- “An Interview with Octavia Butler” by Charles Rowell. Callaloo, Volume 20, No. 1, Winter 1997.

- Charlie Rose, “A Conversation with Octavia Butler.” June 1, 2000.

- Phone interview by Randall Kenan, November 3, 1990.

- “Interview with Octavia Butler” by Joshunda Sanders, Africana.com, February 24, 2004.

- “Is Science Fiction Science?” Closer to the Truth, Episode 1.

Related

Blake Charlton, M.D., Author & Cardiologist Fellow at the University of California, S..

Blake Charlton would appear to have it all. A summa cum laude graduate of Yale University, a graduate of Stanford Medical School, and a published author, whose debut novel, Spellwright, was released to glowing reviews from the science fiction community and the publishing industry at large. The novel was the first of a nearly finished trilogy published by Tor Books. Set in a world where words can be physically peeled off a page and used to cast spells, Spellwright relates the misadventures of a wizard named Nicodemus Weal, who has a gift for producing magical language, but a disability that makes any text he touches misspell, with devastating consequences.

Read More

Max Brooks, New York Times Best-Selling Author

Max Brooks, the #1 New York Times bestselling author of The Zombie Survival Guide (Three Rivers Press) and World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War (Crown) knows a little something about this. Yet he would argue that his years spent at the Center for Early Education in Hollywood as a young boy with dyslexia left him riddled with anxiety and self-doubt that shadows him to this day. “It was a slog,” he says simply.

Read More

Jeanne Betancourt, Children’s Book Author & Screenwriter

Jeanne Betancourt is the author of 75 novels for children and young adults; more than a dozen film and television scripts; and an adult nonfiction book. She is a recipient of the American Psychological Association’s National Psychological Award for Excellence in the Media and several Children’s Choice Awards. Betancourt also received six Emmy Award nominations for her After-School Specials, written for ABC Television and featuring teens dealing with critical social issues.

Read More

Gareth Cook, Pulitzer Prize-Winning Journalist

Gareth Cook is a journalist and is currently a writer for The New Yorker and a series editor at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. He spent seven years as the Boston Globe’s science editor reporter, and during that time won the Pulitzer Prize (2005), the National Academy of Sciences Communications Award (2005), and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Ocean Science Journalism Award (2005). In awarding the Pulitzer to Cook, the judges commended him for “explaining, with clarity and humanity, the complex scientific and ethical dimensions of stem-cell research.”

Read More